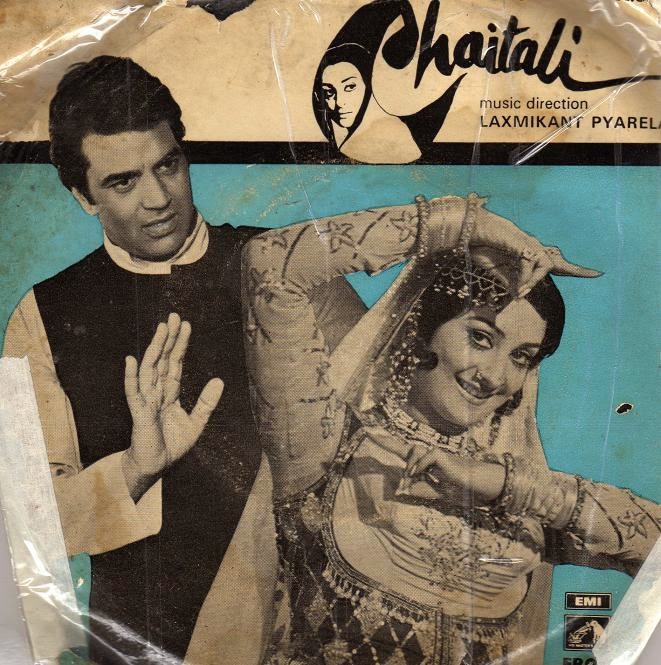

This is a mid 1970s movie

starring Dharmendra and Saira banu in lead roles, and directed by none other than

Hrishikesh Mukherjee, a man who helmed arguably some of the best Hindi movies

made ever. There is another great matter of prestige attached to this feature,

that of it being a Bimal Roy production, albeit posthumous. Bimal Roy, who

himself arguably made some of the best Hindi movies ever, is also seen by many

as the precursor to Hrishikesh Mukherjee, who he mentored along with a man

called Sampoorn Singh Kalra, better

known as Gulzar. So it will be fair to say that ‘Chaitali’, as a movie, boasts

of some enviable pedigree. And yet, it is one of those criminally under-seen

movies, reflected in just a handful of ratings it has garnered on Imdb (less

than 20 on last count). It might have been a commercial failure at that time, but

does it deserve the obscurity that it is shrouded in today? For sure not, as,

though the film is not faultless, it is still a reasonably engaging dramatic

feature that makes a social comment on delinquency, forgiveness, and redemption.

Adapted from a Bengali short

story of the same name, Chaitali inhabits a world that is much different from the

general Hrishikesh Mukherjee fold, wherein most of his movies stayed away from depicting

the darker strata of our social order. The narrative is centered on Chaitali (Saira

Banu in the title role), a woman who has been forced by her circumstances and her

unfortunate upbringing to occupy a space that constantly haunts her, but from

which she not being able to escape. Creating a stark contrast, her life merges

with a more typical Hrishikesh Mukherjee middle-class urban household, full of

family values and righteousness. The first few minutes of the movie establish

this moral rectitude and bonhomie of this family, headed by a kind matriarch, and

assisted by that ever cheerful and passionately loyal servant (Asit Sen yet again). The tone and

tenor of the film then changes considerably when Chaitali enters the household,

guiltily taking advantage of goodness of the elderly matron, with the intention

of swindling some money. All this while, the younger son of the family Manish, (Dharmendra

in a mostly subdued role) is aware of the reality of the woman, but takes pity

on her circumstances, apart from developing a soft corner for her. The drama later

shifts to a religious sanctuary on the hills, where Chaitali shares her life

story honestly with Manish, who gets utterly shaken by the grimy details of her

upbringing, which include a criminally inclined father on the run, a brothel, many

lecherous eyes eager to pounce on her adolescence, and a suitor (played uninhibitedly

by Asrani) who is both a danger and a comfort to her in the murky vicinities of

her life.

Throughout the story and its

dramatic last act (the best executed out of the lot in my view), Chaitali comes

across as a highly complex character, both repulsed by and dependent on crime

and delinquency. And this confusion, somehow, gets reflected in the treatment

of the film, with its highly uneven tone oscillating between glimmers of hope

and pits of hopelessness. Dharmendra’s part is under-cooked and not well

defined, with neither his motivations, nor his intentions, and nor his beliefs,

coming out on screen clearly. This in some ways gets evened out by strong

subsidiary characters- chiefly the lawyer elder brother (who gets a lot to do

in the last act) and his wife (Bindu in a meaty part, but hamming it up

completely).

The music of the film, much like

the film itself, is not popular at all. There are just three songs, and seen in

isolation, two of them are pleasant enough. But none add to the movie in any

which way; this lack of memorable tunes another reason for the oblivion the

film finds itself today.

Signing off with a vintage 'on-the-set' still from the filming of an outdoor shot from the movie:

|

| http://cinegems.in/dharmendra-hrishikesh-mukherji-durga-khote-and-saira-banu-on-the-locations-of-chaitali-1975/ |